The longest eight seconds one can experience—if you even make it that far—happens while mounted atop a giant, seething bull focusing its entire tonnage on turning brutally jolted riders into human projectiles. The vast majority of us know this vicariously from outside of the ring (and we’re good with that). Professional bull riders, on the other hand, “approach their seemingly insane job with an ice-calm self-assurance in the most audacious and dangerous game of chicken imaginable,” writes Andrew Giangola. “But these cowboys aren’t crazy. They are alive.”

In his new book, Love & Try: Stories of Gratitude and Grit in Professional Bull Riding, Giangola offers a rare, behind-the-scenes look at America’s most feared, revered, and oft-misunderstood man-versus-beast sport. Harrowing and humorous, tragic and triumphant, compellingly human, this collection of true tales from the wild world of bull riding runs the gamut. Stories delve into lives of the whole cast and crew: from fallen riders determined for one last shot to stoic doctors patching up their battered patients for another day in the ring, crew members caring for beloved beasts to a 13-year-old determined to become the first girl on the Professional Bull Riders circuit.

“The bull riding community is united by a love of one another, the sport, and its animals,” says Giangola. “The ‘try’ behind every eight-second ride is a dogged mantra in everything they do.” During Western culture’s latest popularity surge, Love & Try is a timely introduction to the wildest sports scene in these storied parts. Get a taste of what the book’s all about below.

EXCERPT

An Improbable Story of Celebrity Stardom

“The first piece of good news was that I wasn’t going to die,” said the bull rider, on his back in the hospital bed, immobilized in the way you’re kept still to prevent a move that will kill you. “Then I found out that one day, I’d be back on my feet. The minute the doctor said I’d walk again, I wanted to jump right out of this bed and dance.”

In 2016, Bonner Bolton was an up-and-coming bull rider with a great future. He had won a title in CBR (Championship Bull Riding) in 2007 at the age of 20 then moved to where the big boys get on the rankest bulls – the PBR. After finishing fourth at the 2015 PBR World Finals, he came into the following season on fire, leading the season opener in Chicago. On Championship Sunday, the 28-year-old never felt better, physically and mentally. He always had the swagger. Now he was earning the right to display it. He would be first to ride in the second round at All State Arena, the position bull riders call “The Gunner.”

“There’s extra pressure being The Gunner. The moment is a little bit more intense to start the show with a bang. But you love it. Everyone wants to be that guy,” Bolton said.

He had last seen the bull, Cowboy Up, in 2015. Most riders don’t get analytical about their bull matchups. These are, at their core, wild beasts. But any creature, even one whipping with the ferocity to sling a rope of snot twenty yards, has tendencies. Bonner knew enough about Cowboy Up to believe the bull fit his style. It was a great matchup for a dance he hoped would lead to winning his first elite series event.

Bonner wrapped his hand in the bull rope and nodded his head. The gate swung open, and the duo blasted from the chutes. He held his rope tight. Above his sticky gloved hand, the bulging bicep that had been surgically reattached after being torn clear from the bone on a rank ride was doing its job.

By the time the gate clanged shut, Bonner was up on the bull, centered, seemingly a split second ahead of each of Cowboy Up’s violent moves. Bull riders don’t think it through. There’s no advance planning. Not a lot of game film or X’s and O’s. Spend any time on a bull anticipating his next turn to strategize your counter move, and you’re dumped. Maybe stomped. It’s all muscle memory; reactions are instinctive. Riders who think too much are on the ground before they even can process what they’re trying to figure out. Use your head, and you’re on your head.

Bolton’s body was matching the bull’s twists and kicks. The 8-second horn sounded, signaling a successful qualified ride. In that instant, it appeared the night’s drinks would be on him.

“Move for move, the ride was perfect,” he remembers. “When it came time to come off, I wanted to get out away from him. But he rolled me off his back, and the momentum shot me straight up instead of away from him.”

Bull riding is a sport in which an athlete can hit the proverbial grand slam home run and wind up in a wheelchair. He can score the game-winning touchdown and never walk again. A bad dismount after correctly riding your bull often doesn’t end well. Sometimes it can be disastrous.

Bolton was launched like a midlife crisis billionaire’s rocket.

He spiraled up out of control and landed on his head, pile driving perpendicular into the dirt.

“It’s like someone grabbed a baseball bat, took a swing, and lit me up,” he said. “I heard a sickening crunch. I can see bull’s feet stomping around. I’m thinking, ‘He’s gonna get me and I’m gonna die.’ Guys do die in the arena, and their faces started flooding into my head. My life is going to end right here right now. I’m never going to see my family and friends again.”

In the ensuing years, Bonner had had time to think about the next few seconds and what could have been…but, fortunately, didn’t come to pass.

“The real miracle is the bull goes over me and all four feet lightly graze around me. He even puts his head on me, like he’s going to mash me into the ground. He has me dead to rights. But he holds back. I think he sensed I was hurt; he didn’t want to kill me. My life in his hands, and he decides to spare me – a magical, unexplainable thing, right? The bull fighters are jumping in, and the bull miraculously steps around me. I believe there was an angel over us right there.”.

He looked out at his arm stretched across the dirt. It was like observing someone else’s limb. It wouldn’t move.

“My mouth is full of dirt. I can’t feel anything in my body. I can see my hands out in front of me, but I can’t feel them. I lift my head a bit and think, ‘Maybe I’m just knocked out and shit’s not functioning.’ I finally put my head back in the dirt. The medical staff rolls me over. The looks on their faces are devastating. I know it’s bad.

“I’m strapped to the backboard. They’re trying to get the dirt out of my mouth. Into the dark ambulance, they’re closing the doors on me. It’s Chicago in January and it’s cold and it’s getting harder to breathe. All my friends, the other bull riders, still have to ride. It’s not like they can jump down and skip out on the competition. We’re all riding to split 50 grand that day.

“Todd, the team Chaplain, rides in the back of the ambulance, hauling me off to the hospital to save my life. Todd keeps telling me: ‘breathe, breathe breathe.’ I’m remembering my yoga classes, trying to breathe. I’m trapped in a body that’s now just a shell, telling, pleading to God, ‘If you’re not taking me home today, I really would like to use my arms again to wrap them around the people I love and let them know how much they mean to me.’ Stuff in your life becomes clear then. It’s the people you love and that love you who matter most. That’s all I can think about: wrapping my arms around my loved ones – just hoping I can have that chance.

“I am fading in the ambulance, and they give me an adrenaline shot. Todd was good to stay with me at the hospital. Then my buddy Douglas Duncan comes. Stetson Lawrence and Tanner Byrne from the tour stop in and give me some humor to keep my spirits up and stay with me through the night. I remember all of us crying in the room. None of us know if I’ll be able to walk. Everyone’s thankful I’m not dead. I’m concentrating and trying to get feeling in my hands. Finally, it feels like a wave in my stomach turning over. It scares me. Am I bleeding? Wait. I just felt my stomach. Then my fingers. Then my toes, and I can feel up through my legs and back. I am so stoked. I want to jump out of bed and celebrate. Every doctor who comes in, I’m telling them, ‘You’re gonna walk me out of this hospital’.”

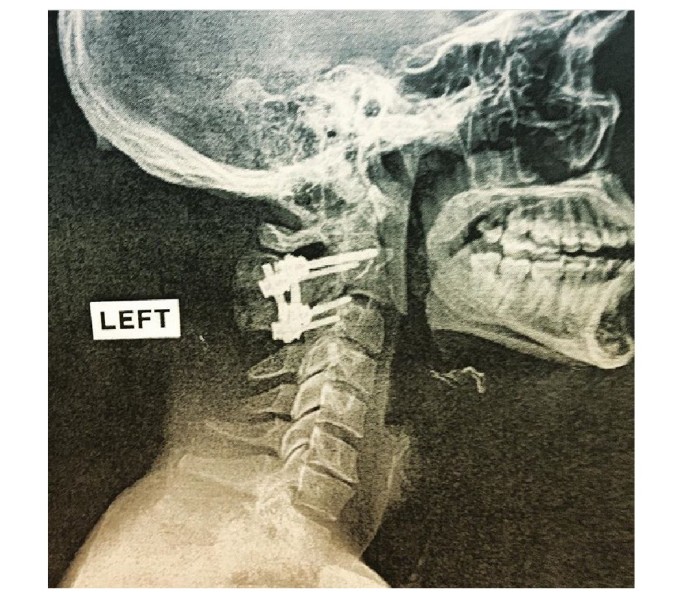

Bolton had shattered his C-2 vertebra – the same injury suffered by Christopher Reeves. However, the famous actor had transected his spinal cord when thrown from a horse. Superman would never walk again. Bonner was luckier. His nerves weren’t cut. He had only badly bruised his spinal cord. It could heal.

He would have spinal fusion surgery. Four talented doctors working six hours fused his C-1 to C-3 vertebrae. Four days after the surgery, he slowly got on his feet. He’d learn to hold a fork again. He was signed by IMG Models, became the face of a new Tom Ford cologne, and 14 months after the accident competed on ABC’s hit show “Dancing with the Stars.”

He’d meet new people, travel to distant places, see the world.

Bull riding is the domain of the relentlessly optimistic. Anyone harboring the notion he will be able to tame a beast more than ten times his size and consistently walk away, unharmed, is awash in sunny delusion. There are no unscathed bull riders.

Some pay the rest of their lives. Some pay with their lives. And then sometimes, after a scary bad injurious wreck, a bull rider will get lucky. His reprieve defies explanation. If’s God’s dirt they play in. Maybe He gets to decide.

For the fortunate bull riders given a second chance, getting knocked down doesn’t define us. What counts is what we do when finally getting up.

Love & Try: Stories of Gratitude and Grit in Professional Bull Riding by Andrew Giangola is available at amazon.com and PBRShop.com with proceeds helping pay the medical bills of injured bull riders.

Comments are closed.